CNN

—

In 1970, more than a quarter of American workers held jobs in the manufacturing sector. Today, it’s only about 8%.

The Trump administration says sweeping tariffs will reverse this decades-long decline. But a vision of reinvigorated factory towns and assembly lines that defined America 50 years ago may be out of step with the realities of 2025.

One of the tariff plan’s architects, White House senior counselor Peter Navarro, says the plan’s “endgame” is “to fill up all of the half-empty factories that now are operating at low capacities around Detroit and the greater Midwest area.”

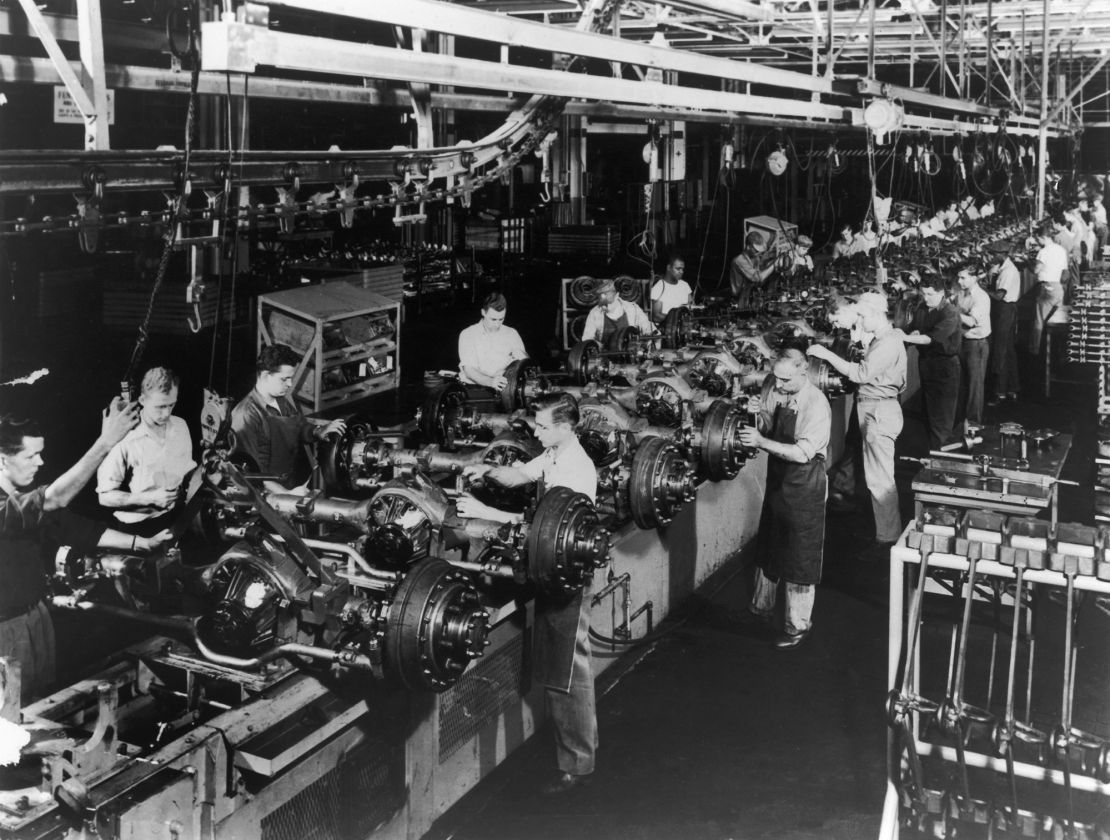

Yet America is far different now compared to the Rust Belt’s glory days five decades ago, when millions of workers were employed to perform specific tasks along assembly lines. Today, in an age of automation and artificial intelligence, factory floors are increasingly filled with robots doing that work instead. That means new and reopened US factories will require fewer workers with more specialized skills.

“The job has very much changed, and yes, there has been a dynamic change in the number of workers needed to it,” said Carolyn Lee, the executive director of the Manufacturing Institute, the workforce development and education affiliate of the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM).

That means the president’s tariff policies, which have been met with resistance by some in the business community and have roiled global stock markets, may only be one piece of an effort to usher in the manufacturing renaissance the Trump administration hopes for. If tariffs successfully push companies to expand their manufacturing capabilities in the US, experts say the challenge will be training Americans to work in modern manufacturing roles — and getting them interested in doing so.

‘Mismatched’ skills

The story of the long, slow loss of manufacturing jobs has loomed large in the US. In the decades after World War II, the US led the world in manufacturing. But over the lnufast 50 years, those jobs have largely moved abroad, and many US factories shut down or stalled, devastating the economic prospects of entire towns and cities in the country’s Rust Belt.

Trump has long railed against the loss of America’s manufacturing prowess, and last week he used it as both a backdrop and a rallying cry whenannouncing the most extensive tariff package in at least a century: a baseline 10% tariff applied across all countries, with even higher rates for the 60 countries Trump’s administration deemed the “worst offenders.”

“American steel workers, auto workers, farmers and skilled craftsmen… They watched in anguish as foreign leaders have stolen our jobs, foreign cheaters have ransacked our factories,” Trump said during the announcement from the White House Rose Garden last week.

It’s still up for debate whether free trade is predominantly to blame for the decline in US manufacturing, though, as several studies have pointed to automation leading to more job losses than outsourcing.

In 1960, workers set a final drive assembly in a Chevrolet factory in Cleveland.

Even so, the US manufacturing sector had been on a modest rebound before Trump’s tariff announcement. Several companies — including Nvidia, Apple and Stellantis — have announced investments in American manufacturing in recent months, for which the White House took credit.

But with the unemployment rate at 4.2%, there are more open manufacturing jobs than there are willing Americans to fill them.

As of February 2025, there were 482,000 manufacturing job openings, according to the latest Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey. In a report from last year, NAM estimated that there would be 1.9 million unfilled jobs in manufacturing by 2033.

If tariff policies push manufacturers to return to the US, the number of unfilled jobs will likely be even higher, said NAM’s Lee.

Many modern manufacturing jobs will require knowledge of software, data analytics and coding, Lee said. Other positions will require workers who can repair the robots on a factory floor. While many of these jobs won’t necessitate a college degree, they do require certifications and training, she added.

“There’s no one kind of manufacturing job, but the thing that is common to every one of these jobs is that they will require skills,” said Lee. “The majority of the jobs in the sector are not entry-level jobs.”

Olaf Groth, who teaches about the future of the global economy at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, said that he agrees with efforts to reshore manufacturing, but they should be coupled with efforts to ensure America’s workers are prepared for the work.

“The skills US workers have are mismatched for manufacturing right now,” Groth said. “What we need to do is lift the majority of American labor from mid-skilled to high-skilled.”

Uncertainty in the age of AI

Meanwhile, critics say tariffs may hurt many of the workers they claim to protect. Higher tariffs often translate into higher prices, which often hit lower-income families the hardest.

“At the end of the day, tariffs are a tax on imports,” a February note from JP Morgan read. “The tax incidence nearly always falls on domestic sellers and consumers, not foreign producers.”

When Trump announced tariffs on $34 billion worth of imports from China during his first term in 2018, Ravin Gandhi, then the CEO of GMM Nonstick Coating, a supplier of nonstick coatings for cookware, was a vocal opponent of the policy, arguing the tariffs would make his products more expensive for American consumers.

Gandhi left his role at GMM last year to work in venture capital investing. Since then, his opinion on tariffs has evolved. He now supports the president’s efforts to bring manufacturing back to the US through tariffs.

Gandhi said there was one theme he had been hearing from friends and colleagues: “Robots and automation.”

Workers load a part as robotic equipment assembles R1T truck bodies in a marriage line on April 11, 2022, at the Rivian electric vehicle plant in Normal.

“I have so many friends who are manufacturing entrepreneurs, and they are raving about the cost savings that they’re seeing as they start to automate,” he added. “These are machines. They don’t need breaks. They don’t need Christmas off.”

Gandhi said that he had already seen automation replace some of GMM’s manufacturing jobs before he left his post as CEO, but he remains optimistic that new technology will usher in new kinds of jobs for American workers.

“I’m a techno-optimist. I do believe that five years from now, there are going to be wide swaths of jobs that don’t exist today that you can’t even fathom,” he said.

It’s a question that extends beyond the Rust Belt. Artificial intelligence threatens to disrupt a significant number of American industries, not just manufacturing, and many experts are pondering which types of jobs will be needed amid a technological upheaval. A January World Economic Forum survey found that 41% of employers across all industries intend to downsize their workforce as AI automates certain tasks.

“We need to define what are the impacts of industrial AI and what those impacts will be on workers and skills,” said Lee of NAM. “In the absence of knowledge, I think there’s a lot of fear and worry. We need to be able to help train the people in the skills they’ll need.”